Trying to work his magic again

Nearly 25 years after delivering the NBA to Orlando, Pat Williams makes a pitch to bring Major League Baseball to town

They call themselves the Orlando Dreamers and, at this point, Major League Baseball in Central Florida is just that—a dream.

But in nearly 60 years as a Baseball and NBA executive, Pat Williams has made dreams come true before.

With Commissioner Rob Manfred intending to add 2 expansion teams in the next several years—and with the future of the Tampa Bay Rays very much up in the air—the man who founded the NBA’s Orlando Magic in 1989 is hoping to work his magic once again.

While Charlotte, Las Vegas, Montreal, Nashville, Portland and Salt Lake City publicly emerged as early contenders for expansion or possible franchise relocation, Williams and his group have been quietly working for the last 4 years to gauge the feasibility of building a ballpark and bringing a team to Orlando.

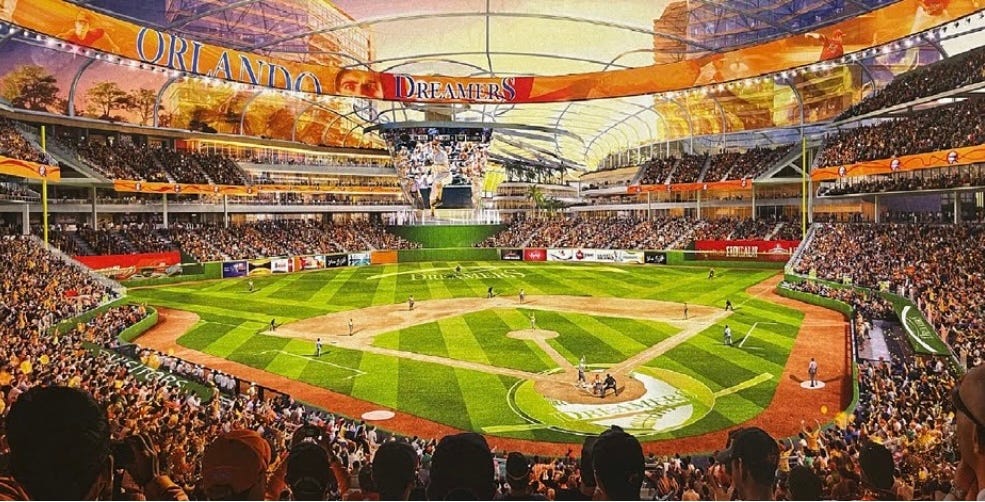

At a Tuesday press conference, Williams unveiled artist renderings of a proposed $1.7 billion ballpark complex, not downtown near Amway Center and Camping World Stadium but on 35 1/2 acres in the heart of the city’s tourist district. The proposed domed stadium, which would hold approximately 45,000 fans, would be part of a ballpark district that would also include retail shops, restaurants, office space, a hotel and parking garages.

The ballpark would be owned by Orange County, but the Dreamers’ proposal calls for $700 million in private funding, which, the group says, would be the most private investment in a publicly owned facility in the history of Major League Baseball.

Williams and the Dreamers hope the remainder of the funding will come from the county’s Tourist Development Tax (TDT), a resort tax on tourists that over the years has helped fund facilities such as Amway Center, Camping World Stadium, Dr. Phillips Performing Arts Center and the Orange County Convention Center.

The county has set records for TDT collected in each of the last 14 months.

In making his pitch to bring the big leagues to town, Williams stresses Orlando’s rapid growth “in 4 directions,” with estimates indicating that an average of 1,000 people a day are moving to Central Florida. That’s on top of the 75 million tourists who visited Orlando in 2022, most of any city in the United States. And that number is expected to spike over the next decade with the upcoming opening of Universal Orlando’s 4th park and the anticipated expansion of high-speed rail service to the area.

Who’s up for Disney World, Universal or SeaWorld by day and a big league ballgame by night?

The Dreamers’ web site suggests that if only 4 percent of the city’s tourists were to attend one game (one out of every 25 visitors), the Orlando club would have the 6th-highest attendance in MLB before selling a single ticket to local fans.

As for the rest of the Dreamers’ pitch:

Orlando is the 17th-largest media market in the U.S., the largest that doesn’t already have a major league team. It’s larger than 9 current ML markets.

With a 2.3 percent annual growth rate, Orlando has one of the fastest-growing populations in the country.

The average age of city residents is only 33, making Orlando the youngest major city in Florida.

The takeaway: The Dreamers contend there is a lot of room for growth.

So how does this actually work?

What Commissioner Manfred has said all along is MLB needs to resolve the ballpark situations in Oakland and Tampa Bay before turning its attention to expansion.

Some progress is being made in that regard.

While nothing is finalized, the Athletics are deep into negotiations with the city of Las Vegas and the state of Nevada to move the club to a new ballpark on the Vegas Strip.

That would do 2 things:

First, it would resolves the Oakland half of the “Oakland and Tampa Bay situations” and, second, it would remove Las Vegas from the expansion mix.

As for the Rays, the latest news is that owner Stuart Sternberg is hopeful the team, the city of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County can come to agreement by the end of 2023 on a deal to build a new ballpark and development project adjacent to where Tropicana Field stands.

But he’s been hopeful before, and the clock is ticking faster than ever with the Rays’ current lease set to expire at the end of the 2027 season.

Sternberg says he’s focused on St. Pete, and “We seem to be making progress.” But he also says he’s continuing discussions with the city of Tampa.

As the Marlins have demonstrated over 11 seasons and 2 owners, building a new ballpark in a market that has historically not drawn well is no guarantee of success. The Marlins remain near the bottom of MLB in attendance (currently 29th out of 30, where they finished last year), and any revenue gains they may have made in more than a decade in their new home haven’t resulted in a payroll that has given them a chance to compete.

The Marlins have the worst record in MLB since the day they moved into their new ballpark, finishing below .500 in every full season since the park opened in 2012.

When I worked with the San Diego Padres in the 1990s and the club was waging a political campaign to secure the public portion of the money in the public-private partnership that built Petco Park, club President Larry Lucchino talked repeatedly about the need to build “the right ballpark in the right place.”

It can be argued that the Marlins built the right ballpark, but in the eyes of many fans, it was not built in the right place.

Would a new Rays ballpark adjacent to the Tropicana Field location in St. Petersburg also be the right ballpark in the wrong place? The region’s historic issue has been fans in Tampa saying they’re unwilling to cross the bridge to go to games in St. Pete.

The Rays have won. They still haven’t drawn. Does a new ballpark in St. Petersburg change that calculus?

Many in the region believe the Rays’ best chance for long-term success is a ballpark in Tampa. But that doesn’t seem to be an option at the moment.

So what if both St. Pete and Tampa fall through?

That would appear to be Orlando’s best shot.

With the horrific attendance woes the Marlins and Rays have endured over the entirety of their existence, it’s virtually impossible to see MLB considering a 3rd franchise in the state of Florida as a viable option when other alternatives exist, particularly when the proposed new ballpark site in Orlando is only about 90 minutes from where the Rays currently play.

But if Tampa-St. Pete is no longer in the mix, moving the Rays to a new ballpark in Orlando would seem like a perfect alternative for several reasons.

Because of Orlando’s relative proximity, you’d have the chance to maintain some percentage of the existing fan base.

If the Rays relocated, the Orlando Dreamers wouldn’t have to pay an expansion fee to MLB (which Manfred previously said would be $2.2 billion), although there could be a relocation fee required. Front Office Sports reported last year that MLB could waive the relocation fee if the Athletics were to move to Las Vegas. How could there then be a fee to move the Rays to Orlando (or anywhere else)?

And by getting a team that’s already built, they would certainly be much closer to winning from the start in Orlando than if they were building a ballclub through expansion.

What’s next?

The next hurdle Orlando must clear to remain viable and in the mix is to have the Tourist Development Tax greenlit. That verdict is expected to be rendered by the end of July. Without that money, it’s unclear how Williams and his Orlando group can make this work.

But if it’s approved, the dream of potentially bringing Major League Baseball to Orlando—through expansion or relocation—would be alive and well.

THE PAT WILLIAMS FILE

A Wake Forest graduate with a master’s degree from Indiana University, Williams played 2 minor league seasons as a catcher in the Phillies organization, making his professional debut with the Miami Marlins of the Florida State League in 1962.

Worked in a series of front office roles in the Phillies in Twins organizations before being named business manager of the Philadelphia 76ers in 1968.

Served as general manager of the Chicago Bulls and Atlanta Hawks before returning to the 76ers in that role for 12 years. In Philadelphia, acquired Julius Erving and Moses Malone via trade and drafted Maurice Cheeks and Cedric Toney, building the team that would win the 1982-83 NBA Championship. Drafted Charles Barkley before leaving the 76ers in 1986.

Co-founded the expansion Orlando Magic, with the franchise being awarded in 1987 and playing its first game in 1989. Drafted Shaquille O’Neal in 1992, and acquired Penny Hardaway on draft night in 1993. By 1995 had the Magic in the NBA Finals for the first of 2 times.

Led NBA teams to the playoffs 23 times and to the NBA finals on 5 occasions.

Had 19 former players go on to serve as head coaches in the NBA, and signed Billy Cunningham and Chuck Daly to their first coaching contracts. 7 of his former players have been head coaches at the college level.

In 1996, was named one of the 50 most influential people in NBA history by Beckett’s.

In 2012, received the John W. Bunn Lifetime Achievement Award, presented by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame for significant lifetime contributions to the sport.

Served as senior vice president of the Magic until his retirement at the end of the 2019 season, capping more than a half century in the NBA.

One of America’s top motivational speakers, Williams is the author of more than 100 books.

Tampa to Orlando seems the only possibility